Super Resolution Microscopy opened our eyes to biological processes on scales previously hidden from view. At ICMS, researchers keep pushing the limits of SRM and expanding the technique’s possibilities. For those who think this is just another lab tool, think again. The ICMS infrastructure for research and innovation makes sure it’s finding its way into real life applications.

The Netherlands has a rich history in microscopy, with the strongest example being Antoni van Leeuwenhoek who discovered a ‘hidden world’ and pioneered the field of microbiology with his self-made microscope in 1674. Fast forward to the present: researchers at the Institute for Complex Molecular Systems (ICMS) at Eindhoven University of Technology are still leading the way in a specialized field called Super Resolution Microscopy (SRM). The ‘super resolution’-part entails going beyond the diffraction limit; a physical law that puts a limit on the size of objects that can still be imaged. For optical microscopes, this limit is ~200 nm. However, in biology plenty of interesting stuff happens at scales much smaller than that.

‘A single system can lead to groundbreaking work in many different fields’

Lorenzo Albertazzi

To probe further and get a glimpse of these smaller structures, electron microscopy is often applied. Here, electron beams are used with wavelengths 100,000 times smaller than visible light, resulting in a much higher resolution of about 0.1 nm. Unfortunately, electron microscopes require a vacuum that does not permit living objects to be imaged. SRM, on the other hand, allows biological processes to be followed in great detail. It relies on the use of fluorescent molecules that adhere to the imaging target (for example, a protein) and then turning them on and off with a scanning laser. As a result, such objects can be pinpointed with extreme precision and structures are resolved at nanometer resolution.

Super Resolution Microscopy has opened up new possibilities to study biology at nanosized dimensions and has quickly become an indispensable tool for biomedical researchers. It earned three of its pioneers the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2014. But even though commercial SRM systems are available, it is certainly no plug-and-play technology. Still, it requires special skills and experience to get the most out of them.

Pushing the limits

‘We are of course equipped with state-of-the-art Super Resolution Microscopes, but our specialism lies not only in SRM, but more in how to apply the microscopy. In turn, we use this to understand the interactions of materials or biological processes at the smallest scale’, says Lorenzo Albertazzi, associate professor and leader of the Nanoscopy for Nanomedicine-group within ICMS. The versatility of SRM allows ICMS researchers to work on key applications, such as diagnostic biosensing, regenerative medicine materials, and nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery.

‘We continue to push the boundaries of SRM and we continuously invent new methods to study specific biological processes or solve limitations that conventional methods experience’, Albertazzi explains. In his view three important items stand out: sample preparation, labeling, and data analysis. This unique expertise lies with a multidisciplinary team of ICMS researchers, covering physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and computer science. Albertazzi: ‘A single system can lead to groundbreaking work in many different fields.’

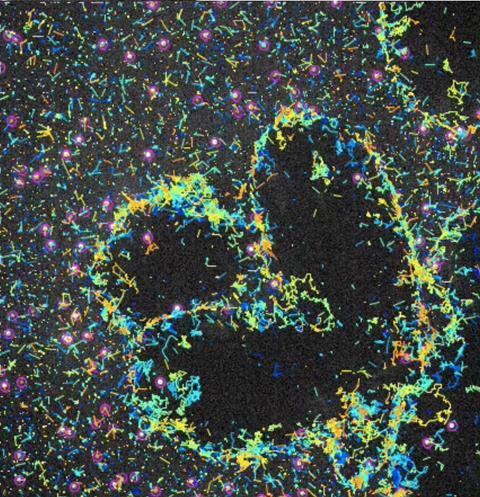

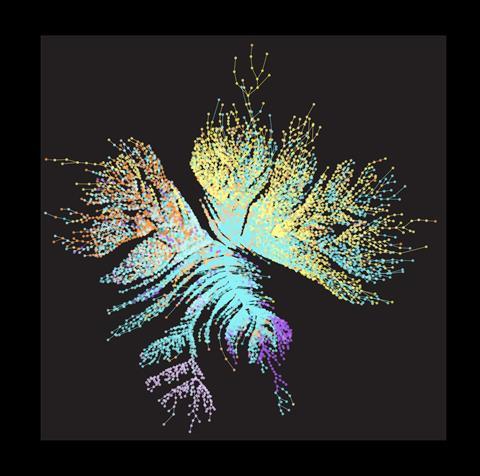

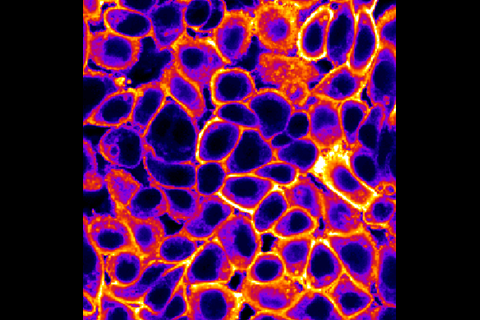

One great example of SRM’s versatile nature is the Single Molecule Localisation Microscopy (SMLM) that the team developed for studying complex interactions between glycans (complex sugars) and lectins (sugar-binding proteins that play a critical role in the immune system’s recognition of pathogens). This understanding is vital for designing new therapies, such as vaccines. In the SMLM approach, glycan probes are linked to a fluorophore and added to the cell medium. The probes bind briefly onto the cell surface, thereby emitting a bright fluorescent light. This gives binding activity information and a location accuracy within 19 nm, resulting in a high-resolution ‘density map’ of the receptors on the cell surface.

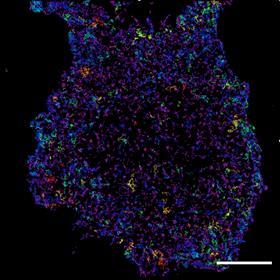

Another example is the breakthrough step the group achieved by developing the SMLM for quantitative imaging. This requires counting the number of labelled molecules, however, existing methods face challenges, because the number of probe fixations is difficult to control, which especially restricts quantitative measurements. Also, the probes don’t always bind to the region of interest. The group solved this by introducing a small peptide-protein interaction pair with encodable genes that are made to genetically fuse to the protein of interest. This results in a highly specific, 1:1 binding ratio that is crucial for quantitative analysis.

‘We connect with industry to get our technology out of the lab and into the real world’

Yuyang Wang

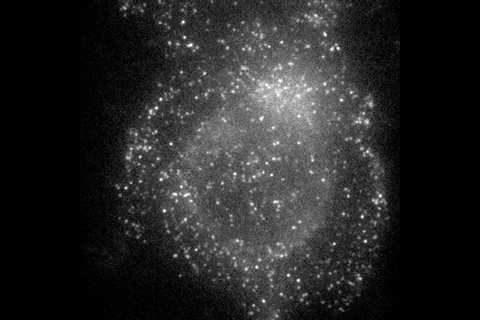

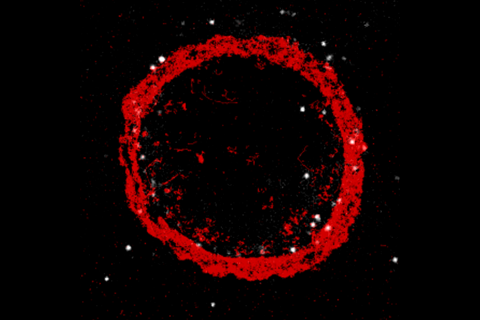

A third example really shows the power of combining two techniques into a super-strong one. Here Albertazzi’s group combined an advanced method called Re-Scan Confocal Microscopy (where sample resolution is pushed by a factor of two) with SMLM to enable the study of protein emulsifiers that are used to stabilize complex oil-water systems in food emulsions. In this case, they specifically visualized the composition of nanosized proteins on individual droplet interfaces. This work provided a real-time and quantitative view of the complex interplay between kinetic and thermodynamic forces that govern emulsifier distribution in food emulsions.

Ice binding proteins

‘We have around 50 active users across all systems, with three ICMS groups developing SRM techniques and close to ten research groups around the university using these’, says Yuyang Wang, founder and lead of the Advanced Microscopy Facility (AMF) at ICMS. The AMF-ICMS is a strong strategic player in the ICMS infrastructure that bridges the gap between technology developers and users and gets the microscopy facilities applied to projects in biosensing and diagnostics outside of ICMS.

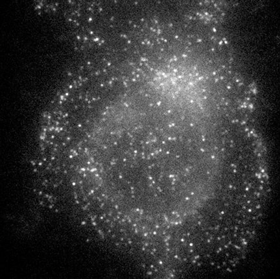

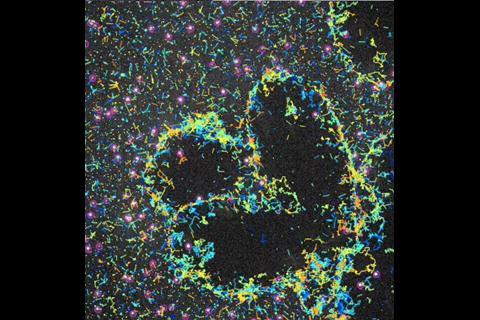

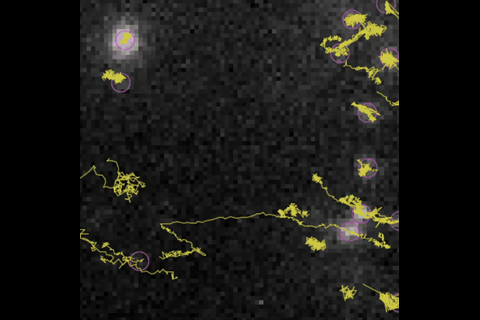

One such user is PhD candidate Sanne Giezen. In her research at the department of Chemical Engineering and Chemistry, she investigates ice binding proteins (IBPs), produced by organisms to survive in extreme cold conditions. The interaction of IBPs with the ice-water interface, which is not yet completely understood, is now visualized using SMLM. In addition, she is setting up a technique to use polarization microscopy to distinguish binding dynamics and affinity between the different ice planes on which IBPs can adhere. However, switching between the two different techniques prevents capturing everything in one event. That is why she, together with AMF-ICMS researchers, is developing a combination of the two techniques. Giezen: ‘If successful, we can gain much more insight into the dynamical processes of IBPs at the ice-water interface.’

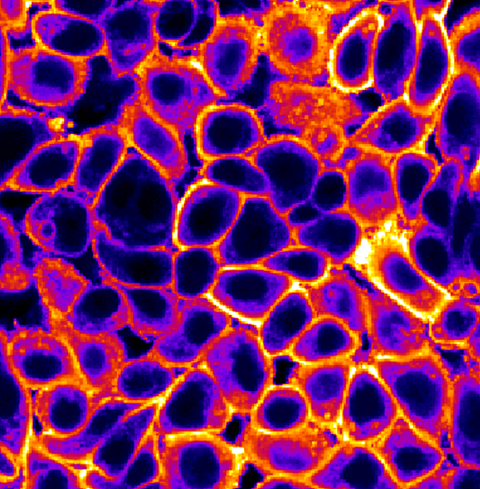

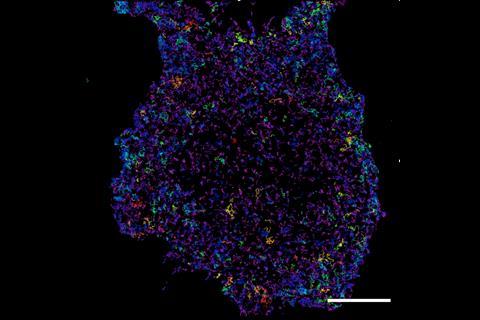

Another user is PhD candidate Esmee de Korver, from the department of Biomedical Engineering. She studies the development of synthetic biomaterials such as mimics of collagen; the protein that provides structure to skin and other tissues in our body. In the future, synthetic biomaterials could replace tissue that is lost due disease and/or surgery, for example in cancer. ‘In my research I study the role of chirality, an important form of molecular rotation’, De Korver explains. She imitates collagen behaviour by chemically redesigning its building blocks, using ureidopyrimidinone (UPy) monomers that have fluorophores attached, and then stacking these into big fibrous polymers. By using SRM she traces their complex movements and interactions with nanometer resolution.

Real world

‘At the AMF we combine ICMS’s academic side with true innovation by connecting with industry to get our technology out of the lab and into the real world’, Wang states. Via their industrial partnership program, AMF-ICMS offers imaging services to companies and maintains strong ties with spin-offs that offer SRM services related to characterization, diagnostics, and biosensing as their product. In addition, SRM co-develops methods for medical use, with a clinical trial currently ongoing where SRM is applied to patient biopsies for diagnostic purposes in precision medicine.

Albertazzi concludes that ICMS continues being at the forefront of research and innovation and keeps raising the bar in their field. It goes hand in hand with applying more and more AI to their data analysis. ‘These developments can help to push the boundaries even further and we are excited to see which new discoveries the field will take us.’

Nog geen opmerkingen