Researchers at Wageningen University & Research have demonstrated that hydrogel microparticles can be used to measure three-dimensional cell movements. You can read about how to make and use them in their comprehensive publication in Nature Protocols.

Cells move during all kinds of processes. But how can you measure those movements? An international team led by Assistant Professor Daan Vorselen (Wageningen UR) has developed hydrogel microparticles that can be incubated with cells to help map their movements in three dimensions — something that was not previously possible.

‘In our lab, we want to find out how immune processes work’, says Vorselen, a biophysicist by training. Nevertheless, he uses chemical strategies to study immune cells. ‘We mainly look at how those cells deal with targets of different shapes and sizes. How does that change their behaviour?’

Eating

The principle that Vorselen and his colleagues use — recording movements using hydrogels — is not necessarily new. ‘In that border area of biophysics, this technique is mainly used to make cells move on a 2D surface.’ First, a hydrogel is made, into which nanoparticles are incorporated. When a cell moves over the gel, it deforms and the nanoparticles move. Using information about the hydrogel’s mechanical properties, you can then calculate the movements and forces involved.

‘This is also done with immune cells, but that’s a bit strange’, Vorselen continues. ‘An immune cell cannot “eat” a 2D surface. When we came across these kinds of studies, we thought: couldn’t we do the same thing with balls?’

Squeeze

It was a nice idea, but easier said than done. ‘We soon realised that this would be challenging’, says Vorselen. The researchers were faced with two major challenges: the synthesis of the microparticles and extracting the force from the deformation.

Particles of 100 µm and larger and nanoparticles are both fairly easy to make. ‘But we wanted particles measuring 10 µm or less, and that’s a difficult size.’ Using an emulsification process and a microfluidic multi-channel membrane produced by the Japanese company SPG Technology, they succeeded in creating billions of uniform particles.

These ball-shaped particles act as force sensors. ‘It’s not a chemical issue, but one of elasticity’, explains Vorselen. ‘When you squeeze or stretch a ball, it takes virtually the same shape, so how can you calculate the forces exerted on it based solely on its shape?’ That was beyond my comprehension, so we collaborated with mechanical engineers Yifan Wang and Wei Cai at Stanford.’

Lucky guess

Despite the challenges, they also had ‘a huge stroke of luck’. Vorselen continues, ‘You also have to determine how rigid to make such a particle so that it both deforms and is eaten by the immune cell. Our first guess at the level of rigidity turned out to be perfect! That made a huge difference, because it could have taken weeks or months.’

It was only when they saw the particles deforming under the microscope that the researchers knew for sure that they were on the right track. ‘Until then, it was speculation. This builds on work I did during my postdoc with Julie Theriot [co-author, University of Washington, ed.], and you always have to make sure that it works in other labs too. But my PhD students Alva Mali and Youri Peeters also succeeded. That’s why it’s so great that we’ve now been able to turn it into a protocol, so we can help others who want to work with it.’

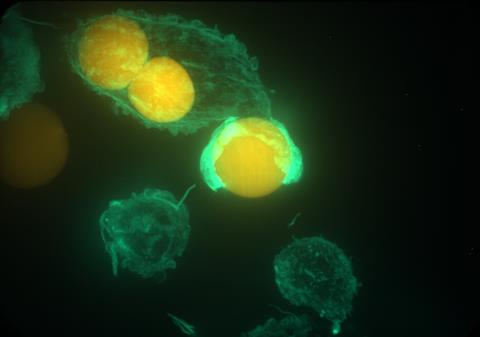

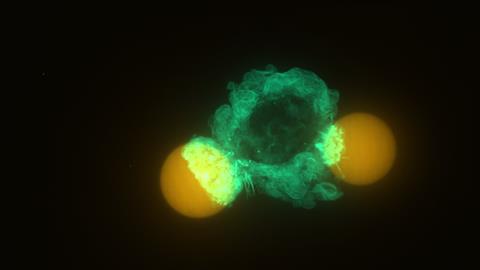

The big advantage of this technique is that you can see not only the forces parallel to the surface, but also the normal forces — something that was not possible before. Vorselen: ‘We see that the cells squeeze the particles, like a boa constrictor or a string wrapped around them. That’s something we didn’t expect, and we don’t yet fully understand why they do it.’

Biomarker

There are interesting applications on the horizon. ‘Think, for example, of a screening tool’, says Vorselen. ‘Other work has shown that the more force an immune cell exerts, the better it is at killing cancer cells. Force could serve as a biomarker for this: this immune cell exerts a lot of force and is therefore effective against cancer.’

However, to achieve this, the throughput needs to be increased. ‘It currently takes fifteen minutes to analyse a single cell. To speed this up, you could sacrifice some detail so that you can measure faster using a simpler method.’

Mali, A., Peeters, Y., et al. (2025) Nat. Protoc., DOI: 10.1038/s41596-025-01281-2

Nog geen opmerkingen