After years of answering questions such as ’Am I doing it right?’, ’Why isn’t it working?’ and ’Could you also…?’, the group of scientists from the Radboud University who invented polyisocyanide hydrogels decided to draw up a protocol that describes absolutely everything. Their work was recently published in Nature Protocols.

’We have been working on this gel for quite some time. The first paper in Nature was published in 2013’, says Paul Kouwer, Associate Professor of Synthetic Organic Chemistry at Radboud University. ‘With this paper, we aim to enable people to modify the hydrogel themselves and use it effectively.’ Consequently, the majority of the paper focuses on how to apply the gel in cell biology.

‘When people use our gel — and they are doing so more and more — I often provide instructions’, says Kouwer. However, despite these instructions being quite detailed, he often receives phone calls saying that it doesn’t work. ‘After asking a few questions, it turns out that they haven’t used the heating plate, for example, meaning they haven’t followed the instructions properly. Perhaps the instructions weren’t clear enough.’

Pride

To prevent this, Kouwer and his team have created an extremely detailed protocol that should answer all questions and cover all gel variations. ‘It has become a bit of a flagship product’, he says with a hint of pride in his voice.

And rightly so, because it took quite a long time to get published for a non-research paper. ‘We submitted our first proposal in November 2023, after one of my PhD students — now a postdoc — suggested we should help everyone who uses our gel by providing clear instructions’, Kouwer continues. ‘We received a positive response from the journal, which meant that it would almost certainly be published.’

However, this meant that they had to review all the data from the ten years during which they had used the gel. Was it still accurate? Did anything need to be remeasured? Were all PhD students using the same protocols? The guarantee of publication kept Kouwer going. ’At times, I was on the brink of despair. It took forever, and then we received about a hundred editorial questions when you would normally only expect ten. But that makes this the best-edited paper I have ever written.’

Guarantee

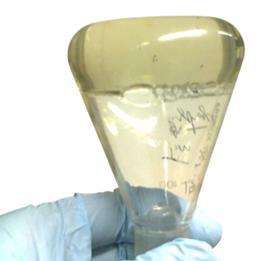

The PIC hydrogel is intended for cell culture, and Kouwer’s team is open and honest in the paper about how to make and modify the gel. ‘We’re good at modifying it, which is why we’re setting up a start-up called SBMatrices to sell modified gels.’

But won’t he be shooting himself in the foot by publishing all these modification methods? ‘I don’t expect so. We did so on the assumption that most users – biologists – would rather buy a ready-made gel than have to modify it themselves. We can also guarantee that it works when we deliver it.’

He will soon be publishing a paper in collaboration with Hans Clevers, who is using this gel in practice. ‘Hans is, of course, known for his organoid research. To grow these, you normally use Matrigel, which is currently the best material for this purpose.’ You take a mouse, implant a tumour, let it grow, and then remove it. Matrigel is that material, and a billion euros and millions of mice are involved.

However, there are major drawbacks, explains Kouwer. ’Apart from the animal suffering, every mouse is different, so Matrigel cannot be uniform. What we have done with Hans is develop a material that works just as well as the animal material.’ Although many gels for organoids have already been developed, it is almost impossible to get the cells to grow properly. ‘That’s why the mouse material remains so popular. After twenty years of organoid research, it would be fantastic if we could present something else that might work even better than Matrigel without involving animals.’

Kouwers’ next goal is to persuade people to try the PIC gel and then provide customer support. ’I hope the company and the team can help with that, and that we can really offer something better. So: Join the transition!’

Nog geen opmerkingen