Biochemists at Utrecht University have developed a fluorescent sensor that makes DNA damage and repair visible in living cells and animals for the first time. In an article published in Nature Communications, the researchers demonstrate how the sensor binds to damaged DNA without interfering with the repair process.

Our DNA is constantly subjected to damage, for example from sunlight or chemicals, or during the replication process. The cell uses various proteins to quickly and efficiently repair the DNA breaks that occur during this process. When this fails, however, it often has adverse consequences. Due to its significant role in ageing, cancer and other diseases, researchers wish to monitor this repair process as closely as possible.

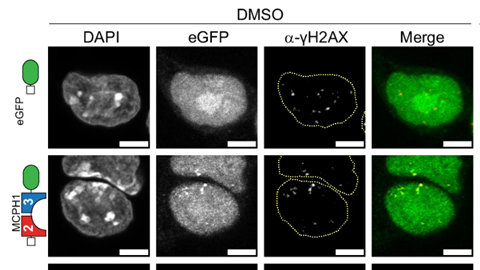

Several techniques already exist to visualise DNA repair. These usually involve a fluorescent protein binding to a break in the double strands of DNA. However, the repair process cannot currently be fully monitored using these proteins. One protein is only usable during certain stages of the cell cycle, while another only provides snapshots of fixed (and therefore dead) cells. Furthermore, some proteins, known as nanobodies, bind so tightly to the DNA break that they do not release and interfere with the cell’s repair system.

However, researchers at Utrecht University have now developed a new fluorescent sensor that enables DNA damage and repair to be observed in living cells. ‘Our technique has no limitations’, says Tuncay Baubec, the biochemist from Utrecht University who led the research. ‘It can detect DNA damage at any time without interfering with repair processes.’

Lego protein

For their sensor, the researchers used a domain from a natural protein — the tandem BRCT domain of MCPH1 — to which they attached the fluorescent label GFP. This domain binds with high affinity to a histone marker characteristic of damaged DNA: γH2AX. It weakly and temporarily attaches itself to the DNA break, causing the damage to light up briefly and allowing the repair process to continue unhindered.

The researchers discovered this domain by testing numerous domains from different proteins. ‘We see protein domains as small building blocks that can be extracted from proteins and reassembled into new proteins, just like Lego’, says Baubec. ‘In the lab, we cloned different domains into synthetic proteins, which we then tested in parallel in our assays. That’s how we stumbled upon this domain, which had the precise selectivity we were looking for.’

Widely applicable

Biologist Richard Cardoso da Silva designed and tested the sensor. ‘First, we looked at which domains bound to the same site in fixed cells as conventional antibodies that attach to DNA breaks. We then investigated how the final sensor functions in living cells when exposed to a number of drugs that cause DNA damage at different rates. We observed the illuminated breaks disappear over time, indicating that the cell was capable of repairing the damage.’

Using fourteen hours of time-lapse microscope videos, the researchers demonstrated that the sensor can reveal the entire process, from lesion to repair, in different cell lines. They also collaborated with colleagues from Utrecht University to apply the synthetic protein to the C. elegans worm, where it caused DNA breaks to light up too. Cardoso da Silva: ‘We show that the sensor can, in principle, be used in different cells and living organisms.’

As a next step, the researchers intend to use their sensor to determine which proteins are involved in repairing DNA breaks. ‘The big question in our field of research is which factors play a role in DNA repair’, says Baubec. ‘This varies depending on the location in the genome and the phase of the cell cycle. With our sensor, we can now investigate what happens and when.’

The researchers plan to extend the synthetic protein with a biotin ligase to fish for the proteins that come to repair the DNA. ‘Methods already exist that use biotin ligase to bind to nearby proteins’, says Baubec. ‘With our sensor, we can label all the proteins in the vicinity of a DNA break. This allows us to identify the important proteins amidst the multitude of proteins present in a cell.’

da Silva, R. C. et al. (2025). Nat. Commun. 16, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65706-y

Nog geen opmerkingen