While many current flame retardants are effective, they contain halogens such as chlorine or bromine, which are not ideal in terms of safety. In ChemCatChem, researchers from KU Leuven, Oleon and Devan present the synthesis approach of a new phosphorous, biobased flame retardant.

‘It all started with sugar chemistry’, says Bert Lagrain, innovation manager in Sels’s group. ‘While synthesising branched sugars (dendroketoses), we realised that the polyol functionality could form the basis of flame retardants.’ This is significant, as current flame retardants are considered substances of (very high) concern, using functional molecules like Bisphenol A. ‘That’s why we wanted to start with safe and renewable building blocks, using green chemistry and avoiding halogenation.’

Opportunity

Ekaterina Makshina, research manager in the same group, adds, ‘We were looking for ways to add value to biomass-related streams. Initially, our target was to transform branched polyols into branched alkanes .’ However, the group recognised an opportunity for other applications in the highly branched structure. ‘Seeing the resulting polyalcohol structure, we realised that our branched polyols can be a good alternative substituting current commercial fossil-based polyols in the chemical industry, such as trimethylolpropane, pentaerythritol, neopentyl glycol, et cetera.’

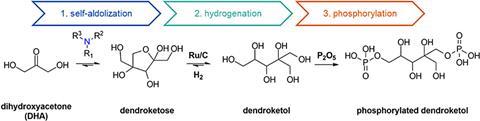

The synthesis of the compound starts with dihydroxyacetone (DHA), which undergoes a self-aldol condensation reaction with triethylamine as a catalyst to form dendroketose. After hydrogenation using a ruthenium catalyst, the resulting dendroketol is phosphorylated to produce the flame retardant. Subsequent testing conducted under EU standard BS 7175 (for bedding materials) confirmed its strong flame-stopping capabilities (see below).

To properly test and validate their compounds and synthesis methods, scaling up was essential. ‘We first produced the branched molecules on a milligram to gram scales, but companies require up to a kilogram for validation purposes’, says Lagrain. However, scaling up can lead to significant challenges. Makshina explains: ‘Our initial lab tests were very promising for several catalytic systems demonstrating high conversions and selectivity, but at larger scale many other parameters start to play important roles, like high catalyst loadings, high dilution of reaction mixture, and high viscosity of resulting polyol after removal of water prior to phosphorylation. We had to re-asses all our results under a completely different angle and look into solutions to overcome the problems.’

Fortunately, they had a great partner in Oleon, a company that specialises in working with natural, renewable raw materials. ‘They took care of the upscaling’, explains Lagrain. ‘It was a rewarding collaboration for us, since the process gave us insight into our laboratory process from an industrial viewpoint, as well as the follow-up after an invention.’

Challenges

The synthesis, scale-up and practical results – ‘It really stops the flames!’ – seem very promising. However, it remains challenging to commercialise the process. ‘There are some major challenges involved in getting this compound through the valley of death’, says Lagrain. ‘You would need an industrial partner willing to invest heavily in setting up the production process. Besides, it is very difficult to create a business plan with a portfolio of only one compound.’

Another issue is the cost. ‘Our molecules are completely new, so you would have to register them with REACH, a costly process’, says Makshina. ‘Moreover, production costs will be significant in the beginning, and one of the starting compounds is difficult to obtain. So our product is very good, but it’s not yet ready for the market.’

According to Lagrain, it’s a general struggle. ‘With novel biobased chemicals, you always have to compete with their petrochemical counterparts. And communication is also important. If we say that our flame retardant is safe and non-toxic, are we indirectly implying that current products are unsafe and toxic?’ He elaborates: ‘This might be an important message for those who want to see renewable chemistry flourish in Europe. It requires significant investment, effort and collaboration with partners because the market is conservative and legislation is expensive.’ A notable example is Avantium: although they are planning their first commercial release for 2026, they have had their well-working compound for decades. ‘Having a good product is just the beginning.’

Matthijssen, J., Rammal, F., et al., ChemCatChem, 17(22), 2025, DOI: 10.1002/cctc.202501139.

Nog geen opmerkingen