For decades, researchers labelling cysteines with methanethiosulfonate groups have observed the formation of a mysterious dimer. Although there are ways to avoid dimerisation, Martina Huber could no longer ignore the issue and set to work with a team from Leiden to unravel the hitherto unknown structure. The answer to the puzzle can be found in ChemistryOpen.

The methanethiosulfonate group is a commonly used functional group in the labelling of sulphur-containing cysteines in proteins, either for spin or fluorescence labelling. The same is true of the MTSL label. It works selectively, but at higher concentrations it forms dimers with itself. This restricts the labelling process somewhat: the concentration of the label must not exceed 200 µM, and since the label is used in a 10:1 excess, the concentration of protein is limited to around 20 µM. While there are ways to prevent dimerisation to some extent, the exact process has remained unclear for over forty years.

‘That kept gnawing at me’, says Martina Huber, an associate professor at the Leiden Institute of Physics (LION). She came into contact with the dimer herself about twenty years ago. ‘Because I did the cysteine labelling “wrong”, I saw the dimer form, and colleagues then gave me tips on how to avoid its formation.’ There seemed to be no interest in what the dimer actually is, but Huber continued to ponder the issue. ‘Surely it must be possible to find out? From a scientific point of view, I find it a bit scandalous that people just shrug their shoulders and dismiss it.’

So she threw herself unsuspectingly into the project. ‘I thought it would be a small project, so I assigned a bachelor’s student to it four years ago.’ But it turned out to be much more difficult than expected. Huber herself has a background in chemistry, but these kinds of organic issues are not her area of expertise. That’s why she called in the group led by Mark Overhand, an associate professor and organic chemist at the Leiden Institute of Chemistry.

‘At one point, I did think, “What have I got myself into?”’ says Huber, laughing. ‘I naively thought it had something to do with the radical, the nitroxide’, she says. ‘But that turned out not to be the case at all, which surprised me.’ The team discovered that it is only the methylsulfoxyl group that reacts. ‘Mark saw the possibility that the proton would be removed, thereby initiating the reaction. What helped with the discovery — and what impressed me — was mass spectrometry.’

You can analyse the isotopic composition of a mass peak to obtain a sum formula. All the authors involved in the project then set out to find a meaningful and matching reaction. The problem was so challenging that it became part of René Dekkers’ PhD research in Overhand’s group. ‘It was great to see those chemists get so engrossed in this, even though it was an obscure problem posed by a bunch of physicists.’

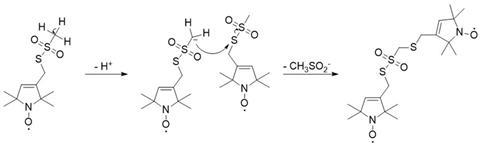

The reaction (see below) begins with a proton (H+) leaving the methyl group. The remaining electron pair then attacks the sulphur atom of a second MTSL molecule, causing the methylsulfoxyl group to leave the molecule and the dimer to form.

Scope

Huber says that the interesting thing is that fluorescent labels with methylsulfoxyl groups also suffer from this problem. ‘But because you use lower concentrations with fluorescence techniques, it is less problematic. This suddenly makes the scope of the problem much bigger, but not necessarily more serious.’ Through this publication, Huber hopes that ‘clever synthetic chemists will come forward and devise an alternative’ to the linking part that is not capable of dimerisation.

Huber praises the ‘courage of the chemists who tackled this problem’. ‘It requires trust in someone who comes along and asks if you can figure something out. I am also impressed by how far organic chemistry has advanced, especially in combination with quantum chemistry. It’s fascinating, even though I’m no longer involved in it myself.’

Passerini, L. et al. (2025) ChemistryOpen e202500314, DOI: 10.1002/open.202500314

Nog geen opmerkingen