Bipolar membranes operating under reverse bias could enable CO2 electrolysis without the need for expensive platinum group metals. However, as researchers at Delft University of Technology show in Nature Chemical Engineering, the membranes are not yet efficient enough for long-term operation.

CO₂ electrolysis is a sustainable technique for converting CO₂ into other carbon molecules using electricity. One of the major challenges for CO₂ electrolysers is the formation of carbonates when CO₂ molecules react with generated hydroxides. Electrolysers consist of a cathode, an anode, an electrolyte, and a membrane that keeps the manufactured products separate. However, the aforementioned carbonates can travel through the membrane and acidify the anolyte (the electrolyte on the anode side). This means that the anodic reaction, which produces oxygen, can only be carried out using an anode made of expensive and scarce platinum group metals, such as iridium, that can withstand the acidic environment.

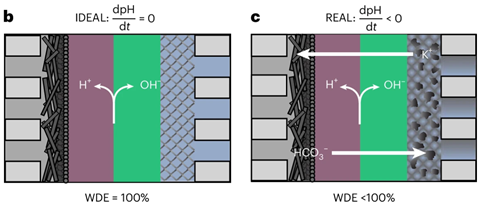

If the reaction could be carried out under alkaline conditions, cheaper, more common materials, such as nickel or iron, could be used for the anode. This can be achieved using reverse-bias bipolar membranes (r-BPMs). Such a membrane consists of two layers: one that allows cations to pass through, and one that allows anions to pass through. Due to the strong electric field between these layers, water molecules break down into protons and hydroxide ions, the latter of which move towards the anode. There, they maintain a high pH, enabling the anodic reaction to occur even without iridium.

Ideally, the pH would remain unchanged, but this would require the r-BPM to dissociate water with 100% efficiency, ensuring that the amount of hydroxide moving to the anode and being converted into oxygen at the anode is equal. Thomas Burdyny’s group at Delft University of Technology has now shown that the water dissociation efficiency (WDE) limits the viability of r-BPMs for CO₂ electrolysis. Undesirable crossover of carbonates, among other things, means that the WDE is too low. Gerard Prats Vergel, a chemical engineer and the first author of the study at TU Delft, explains: ‘The highest WDE we could measure in our setup was 98 per cent. Using a model, we demonstrate that it must be more than 99.8 per cent to create a lasting alkaline environment for long-term industrial operation.’

Anode corrosion

Although r-BPMs promise to solve the problem of carbonates, the Delft researchers questioned the feasibility of this. Vergel: ‘Since membranes are never perfectly selective, the starting point of our study was to investigate the extent to which carbonates that form at the cathode travel through the membrane. What would be the consequences of this?’

The researchers used a membrane-electrode assembly configuration with a nickel anode to measure the WDE of r-BPMs as a function of current density, anolyte concentration, and cation identity. ‘We ran the setup for an hour and measured the crossover of ions by determining the change in concentration at the anode’, says Vergel. ‘We used titration to determine the concentrations of hydroxides, carbonates and potassium before and after the measurements. We quantified that as WDE.’

The researchers discovered that the WDE was much lower than 100%. Vergel: ‘It was closer to 90%, depending on the circumstances. This means that, at a certain point, there are so many carbonates at the anode that it corrodes.’ They also modelled experiments lasting ten thousand hours, demonstrating that a WDE of 99.8 per cent is needed to prevent this corrosion.

Back to the drawing board

Increasing the selectivity of membranes is the big challenge. ‘There is a trade-off between selectivity and electrical resistance’, says Vergel. ‘Making a membrane thicker increases its selectivity and allows fewer carbonates to pass through, for example. However, that thickness also increases the resistance, meaning more energy is needed to enable the reactions.’

For this reason, the researchers predict that r-BPMs will require further innovation, or it will be necessary to return to platinum group metals. Another possibility is replacing the acidifying anolyte periodically, but Vergel concludes that ‘the problem with this is that it increases costs’. ‘According to our estimates, this would account for somewhere between six and 25 per cent of the energy required for a functioning CO₂ electrolyser.’ Therefore, there is still some work to be done before r-BPMs can be applied.

Vergel, G. P. et al., (2025), Nat. Chem. Eng. 2, DOI: 10.1038/s44286-025-00306-7

Nog geen opmerkingen