As budget cuts hit Dutch academia, early-career researchers are starting to feel the impact. Isabelle Kohler contemplates how local decisions, like cutting language support, risk undermining national goals for integration and long-term talent retention. She calls on institutions and policymakers to invest in those people already committed to building their careers in the Netherlands.

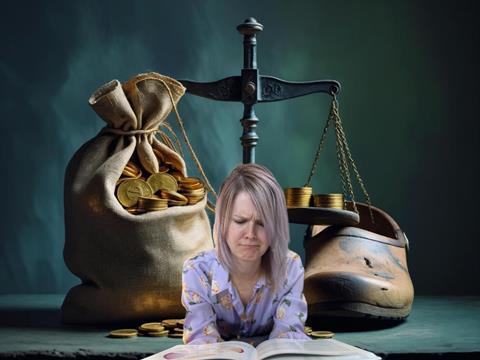

It isn’t a secret anymore: Dutch universities are facing major budget cuts from the government. What used to feel like abstract numbers in policy papers is now becoming visible in our everyday work. Some examples? Reduced research funding, fewer resources for support staff, cuts to basic services like office cleaning and safety presence outside regular office hours. These are just a few of the ways the cuts are starting to show.

As staff members, we try our best to limit the impact of these changes on lab activities so that PhD students and postdocs can continue focusing on their research and professional development. But we have now reached a point where they also start to notice the consequences of these financial restrictions on their work and professional growth.

A recent example from our university illustrates this shift: PhD candidates will no longer receive the 50% discount previously offered on Dutch language courses. This applies to all levels – everyday Dutch, professional Dutch, and preparation for the NT2 State Exam.

This may seem like a minor adjustment in the broader context of budget reallocations, but it carries significant weight – especially when viewed alongside current national developments, such as the proposed Balanced Internationalisation bill (Wet internationalisering in balans). This bill aims to regulate the influx of international students by giving the government more control over the language and accessibility of higher education programmes. If implemented, it will likely lead to the reduction or disappearance of many English-taught Bachelor programs, meaning that non-Dutch lecturers and staff may be expected to teach in Dutch.

From this perspective, the decision to remove Dutch course subsidies for international PhDs is puzzling. On the one hand, we expect them to integrate, adapt, and become capable of teaching in Dutch. On the other hand, we cut the financial support that would enable them to start learning the language early in their careers.

This is a strategic mistake.

If we decrease the chances for non-Dutch-speaking PhD students to learn and master the language during their doctoral training, how do we expect them to be ready to teach in Dutch in the future, should they choose to pursue an academic path in the Netherlands?

This inconsistency may quietly influence hiring practices. Institutions might begin to favour Dutch-speaking candidates at the PhD level, which would be a dangerous shift. Academia has always encouraged (international) mobility because it fuels innovation and brings new talent into the country. If we discourage international candidates at the entry point, we cut off this pipeline. This isn’t just theoretical. Look at the funding structures designed to support this very mobility. The Marie Skłodowska-Curie Doctoral Networks require institutions to hire candidates who have not lived in the Netherlands recently – so chances are high they don’t speak Dutch. The NWO Rubicon grant exists to encourage Dutch researchers to go abroad, and later bring back international knowledge and networks. These funding schemes are built on the assumption that international mobility strengthens Dutch science.

The consequences of these budget decisions reach even further. Many PhD graduates will continue their careers in other sectors, such as government agencies or funding bodies like NWO – where fluency in Dutch is often mandatory or strongly recommended. By restricting access to language training, we not only narrow their future career paths but weaken the broader Dutch research and innovation landscape.

It’s time to rethink our priorities. Instead of spending public money on bringing researchers back from the US or elsewhere, we should consider focusing on those already here. Talented, committed researchers, Dutch and non-Dutch, who have chosen to build their lives and careers in the Netherlands. It isn’t just about helping them feel integrated or welcome. It’s about making sure that Dutch science and innovation remain open, competitive, and connected to the world.

I urge universities to protect and expand language support for international PhD candidates. I also call on policymakers to align integration demands with real, structural support. If we want a strong, innovative, and globally connected academic system, we can’t afford to make short-sighted decisions that undercut the very people who will shape it.

If you are interested in learning more about how to navigate academia, also as a non-Dutch speaker, do not hesitate to join the NextMinds Community! For this, you have plenty of choices: visit NextMinds website to learn more about my work, sign up for the newsletter, and follow me and NextMinds on LinkedIn.

Nog geen opmerkingen