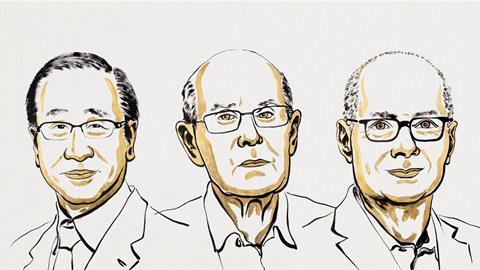

‘Well deserved’ and ‘Bound to happen’ summarize the feeling among the MOF community to the news that the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2025 is awarded to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar Yaghi for their pioneering work on metal-organic frameworks.

‘This choice does credit to the MOF research field’, says Freek Kapteijn, professor emeritus of Catalysis Engineering at Delft University of Technology. ‘Robson laid the foundations, Kitagawa expanded those and studied the fundamentals, and Yaghi explored the possibilities for applications. The result is a new field that offers an endless variety of materials you can create using organic and inorganic building blocks for a wide range of applications.’

Kapteijn’s response is echoed by all the other scientists approached by C2W International. ‘It is an amazing day for the MOF community’, says Stefania Grecea, associate professor at HIMS/University of Amsterdam. ‘Personally, I’m not surprised about Yaghi being awarded, I always thought it was just a matter of time.’ And it takes time to really appreciate the importance and impact of scientific discoveries, she emphasizes. ‘MOFs have been around for decades, but any new research field needs time to develop and mature before we understand its contribution to answering fundamental research questions and the impact it can have in an application area.’

She points to Yaghi’s work in paving the road for those applications. ‘Yaghi demonstrated the application of MOFs in gas storage and separations at the early stage of the research. Yet, translating MOFs from lab to practice and showing how they perform in realistic conditions required a new step: their scale up. This has proven to be a long journey as well.’ Even so, Grecea feels that the timing for the Nobel recognition is opportune. ‘It comes at the right moment, now that MOFs have been shown to play essential roles in solving climate, pollution and energy challenges, such as capture and storage of CO2 and the removal of toxic gases from the atmosphere or of contaminants in water.’

Grecea’s colleague Amanda Garcia, assistant professor at HIMS/UvA was very pleased when she saw the presentation of the Nobelprize, ‘I liked that they mentioned carbon capture in the explanation, because that is what we’re working as well. Even though I my research does not focus on MOF’s, many of my colleagues here at HIMS are working on MOFs, so I was very excited with the news. It is an important recognition for the field because these materials will become very important to the broader chemistry area.’

Rob Ameloot, professor at KU Leuven, also mentions the favourable timing. ‘Right now, the applications of MOFs really start popping up. For example, in the capture of CO2, which is something my group is working on. BASF is currently constructing a scale-up plant for such materials and we are developing the methods to measure the absorption of these MOFs under realistic conditions. Just last week, we published a paper in Nature Communications on chemical sensors that also link to the MOF field.’ The Nobel news was not really unexpected, he says. ‘It was bound to happen and it is a well-deserved recognition for the field and the laureates. Nobody is going to dispute the choice for these three as the founding fathers.’ That is, those that are still among us, because there have been other contributors.

One name that is mentioned more than once in this respect is Gérard Férey, who passed away in 2017. ‘Together with Kitagawa and Yaghi, Férey saw the potential of MOFs and really got this new field off the ground’, says Berend Smit, professor at EFPL in Lausanne. And the field took off like crazy. Smit: ‘Any chemistry journal you open, you’re bound to come across at least one MOF paper. Every day, two new MOFs are created. It is such a huge and fun field to work in, there are so many possibilities for new materials. And now with AI and computational methods, the numbers only grow. Thanks to Kitagawa and Yaghi, I never get bored.’

Nog geen opmerkingen