Current medical implants are often coated with antibiotics or biocides. But these do not work adequately and furthermore leak into the body and the environment. The startup Bioprex Medical makes coatings that solve both problems.

‘A patient receiving an implant, such as a pacemaker or a knee prosthesis, has a 1-5% chance of infection,’ says Ton Loontjens, emeritus professor of polymer chemistry at the University of Groningen. ‘For catheters that remain in place for a month, it is even 100%. Often antibiotics or the immune system itself can handle such an infection, but sometimes the implant has to be removed.’

‘Implant manufacturers are unanimously enthusiastic’

This is inconvenient for the patient and a burden on society, Loontjens stresses. Moreover, such an infection can be fatal for people with poor health. In short, there had to be a solution. Which Bioprex Medical thinks it has found. Loontjens is CTO of this company, which was founded on 28 August 2022.

Stress mechanism

Loontjens worked at DSM for 35 years. There, among other things, he developed ideas on new antibacterial coatings with quaternary ammonium ions as the active ingredient. ‘We have known these ions in solution as disinfectants for more than 80 years,’ Loontjens says. ‘The mode of action is well known: the ions penetrate the bacterial cell wall, causing it to leak. The bacteria then die.’

However, Loontjens wanted to use his ammonium ions not in solution, but fixed on biomedical implants so that they would not leak. ‘My colleagues at DSM strongly doubted whether the ammonium ions would still work. After all, immobilised ions can no longer penetrate? I was confident, though, and decided to continue the research at a university.’

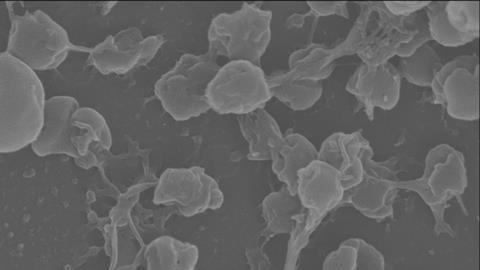

So Loontjens got a part-time position at the University of Groningen in 2005. This paid off a few years later. Because Loontjens and his team discovered that immobilised quaternary ammonium ions kill bacteria via a completely different mechanism. ‘Bacteria are negatively charged by nature,’ explains Loontjens. ‘Now giving the coating a high positive charge via those ammonium ions creates a strong electrostatic attraction. In fact, if the charge density of the ions exceeds a certain limit, the bacterial cells experience such a strong attraction that they are torn apart, so to speak. We launched that principle as the stress mechanism.’

Optimise

Shortly after this discovery, Pieter André de la Porte, director of Zorginnovatie Nederland, contacted Loontjens. ‘He was looking for innovative projects that could become startups and saw potential in the antibacterial coating. From then on, we started the optimisation process.’

This was much needed, as the developed recipe was not yet commercially applicable, according to Loontjens. ‘To give an example: the first coatings took eight days to apply,’ he says. ‘We have since reduced that to eight hours by taking out two alkylation steps and replacing them with an alternative.’

‘Crosslinks give the coating a stable structure’

A lot of research also took place on the coupling agents that connect the branched polymer to the surface. ‘The tree structure of the polymer creates many end groups, which can react with many amino groups and thus give a lot of charge,’ explains Loontjens. ‘In addition, the polymer is crosslinkable, which gives the coating a stable structure. At the tips of those branches you find the immobilised ammonium ions.’

Meanwhile, the researchers tested the coating in at least 10 bacterial species. Of gram-positive bacteria, 99.9% are killed. Gram-negative bacteria sometimes proved more difficult to kill, probably because of their stronger cell wall. ‘But we do have an idea to improve this. A substance that makes the pores in the bacterial wall wider could make them more susceptible to the electrostatic forces.’

Licence or sell

Bioprex’s team now consists of three people: CEO André de la Porte, who provided the funding, CTO Loontjens, the engineer, and recently Jurr van Ramshorst, who handles the business interests. There is also good cooperation with the UMC Groningen. ‘We make the coatings, the hospital does the antibacterial tests. In the meantime, we have become sure of the bactericidal effect. It is now a matter of testing the coating in vivo to check its cytotoxicity. We are doing this in collaboration with the AMC in Amsterdam.’

‘There is a great need for such a coating’

Bioprex does not produce those coatings itself, Loontjens points out. ‘We are now talking to so-called toll manufactorers who will provide catheters and implants with our coating. We are also in contact with implant manufacturers. They are unanimously enthusiastic about the usefulness of antibacterial coatings and are encouraging us to further commercialise our invention. We are now discussing how to make our coating procedure compatible with their processes.’

Eventually, Bioprex wants to either issue licences or sell the whole project to a big company. ‘A big player like that can then really make something big out of it,’ Loontjens argues. ‘I think there will be a lot of interest once we have proven ourselves on the market. After all, there is a lot of need for such a coating. There are more and more antibiotic-resistant bacteria and the development of new antibiotics is disappointing. Our coating can ensure that infections no longer occur, or hardly occur at all.’

Nog geen opmerkingen