If you mutate a certain part of the genome of the blue cheese fungus, blue cheese gets a different colour from the traditional blue, write British researchers in npj Science of Food.

Blue cheeses (such as Roquefort, Stilton and Gorgonzola) are made using the fungus Penicillium roqueforti, which releases blue pigment spores as the cheese matures. But what if you could change the colour? Researchers at the University of Nottingham must have thought so too, because they started tinkering with the mould to see if it could be done.

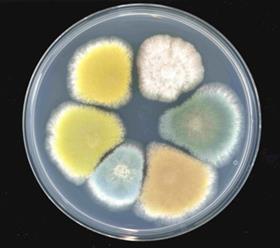

It was already known that there are about six genes involved in the dihydroxynaphthalene melanin biosynthesis pathway that forms the pigments in other fungi of the same family. These are the genes alb1 (albino), ayg1 (Aspergillus yellow-green), arp1 (Aspergillus reddish-pink 1), arp2 (Aspergillus reddish-pink 2), abr1 (Aspergillus brown 1) and abr2 (Aspergillus brown 2).

A similar cluster of these genes was found in P. roqueforti. Using targeted gene deletions, they grew several variants that lacked one of the six genes. This showed that the colour of the spores changed when certain genes were deleted.

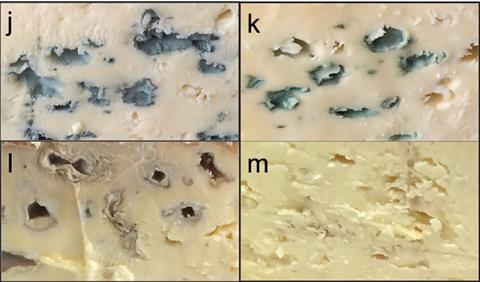

They then used these fungal variants to make cheese. To do this, they had to take a slightly different approach: genetic modification in food is still not generally allowed, so they mutated the fungus using UV light. They selected the most suitable strains with altered spore colouration and, indeed, in addition to the standard wild-type blue cheese, they produced cheeses with green, red-brown and white vains due to the alteration in pigment colour.

When questioned, group leader Paul Dyer revealed that the research did not end there: they tasted the colour variants. ‘We also did some internal University taste trials. And it was interesting – perhaps because of the way we perceive colour – we found that the “light colours” like sky blue were perceived as less strong than the darker blue-greens, and the light Christmas-tree green had a more tangy-fruity flavour, despite the taste being supposedly similar according to our scientific instruments. Thus, we perceive taste with our eyes as well as our tongue and nose!’

The mutations did have some side effects: the flavour profile of cheeses made with the colour derivative fungal strains was slightly different from the standard blue cheese, which could affect the taste or smell. They also produced slightly more of certain toxins on agar plates, but interestingly amounts were lower in cheese than the wild type at levels unlikely to be harmful to humans. The authors see the coloured varieties as contenders to conquer the cheese market, or at least give it a bit more colour.

It remains to be seen what the French think. So far, Dyer has received no angry e-mails.

Cleere, M.M. et al. (2024) npj Sci Food 8(3), DOI: 10.1038/s41538-023-00244-9 (Open Access)

Nog geen opmerkingen