The European Union is about to introduce new regulations restricting the use of the solvent DMF. What does this mean for the industry where DMF is still widely used?

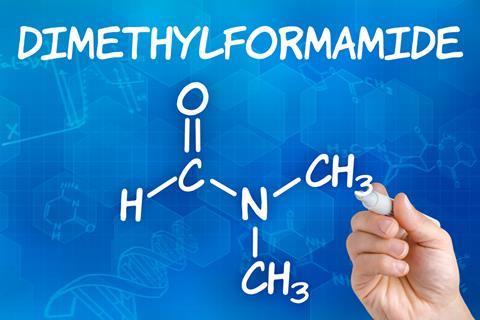

Peptide-based therapeutics are capable of addressing diverse diseases. Both the discovery and manufacturing of these therapeutics heavily rely on solid-phase peptide synthesis. This technology works by adding amino acids to a polymer resin, using orthogonal protective groups to prevent unwanted polymerization. Over several decades, this technique has been refined with N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) as the solvent of choice, which is toxic for both humans and the environment. In spite of this, the aprotic solvent is still widely used, due to the lack of suitable alternative solvents, probably related to the general conservative attitude of the chemical industry. For the industry to change or incorporate new technologies, you need strong economic incentives, supply-chain adaptions, or regulatory changes.

Solution

To reduce the health risks posed to employees arising from DMF, the European Commission has published restrictions to lower DMF exposure limits which will take effect as of 12 December 2023. For now, these regulations mostly impact the large-scale manufacturing of peptides, but they might set a precedent for future restrictions with a focus on environmental concerns, serving as a strong catalyst for change. ‘The industry must seek a resolution – even if an immediate solution remains elusive, documenting the efforts is crucial’, remarked Daniel Sejer Pedersen, Chemical Development Specialist at Novo Nordisk.

Jonathan Collins, Vice President of Business Development at CEM Corporation, adds: ‘In general, we see the restrictions as positive, encouraging companies to innovate towards a more sustainable industry. Innovation will require an upfront cost, but is essential to jump the obstacles of performance and cost achieved with DMF.’

To prevent the restriction from hampering the global competitiveness of the European peptide industry, it is evident that innovation will lay the foundation. Looking from an industrial standpoint, Jonathan Collins says: ‘At CEM, we have focused on two areas of innovation. The first is trying to greatly reduce the amount of solvents needed. The second is to explore alternative approaches to SPPS that would allow greener reagents and solvents to replace the traditional ones.’

Binary solvents

Their latest innovation, which will be released later this year, is a re-engineered SPPS process that completely removes the need for any washing after all coupling and deprotection steps. This new process does not cause any appreciable change in performance and works on proteins approaching 100 amino acids. ‘We believe this to be a significant breakthrough that can serve as a new general process for SPPS and be applied immediately.’ It massively reduces (> 90%) the solvent needed for SPPS and works not only with DMF but also with other greener solvents such as N-butylpyrrolidinone (NBP; TamiSolve).

Novo Nordisk aims to remove all substances of very high concern from their manufacturing processes, including DMF. ‘We searched for various binary solvent mixtures as potential alternatives for SPPS’, Sejer Pedersen says. ‘While unmixed solvents are preferable for handling and recycling, the versatility of binary solvents is useful throughout the SPPS cycle. We found that the binary solvent mixture DMSO with ethyl acetate effectively resolves the toxicity concern. For new pipeline projects, we will use these solvents during development and ultimately for commercial manufacturing.’

Alternatives

The problem, however, is multifaced, Sejer Pedersen continues. ‘SPPS still is a wasteful process in terms of carbon footprint and solvent use and should be considered a global problem, even though it complies with the upcoming European restrictions. The entire world should be looking for a completely new peptide synthesis platform, but that won’t be easy.’ Still, there are already some alternatives like water-based SPPS, tag-assisted peptide synthesis, and peptide ligation approaches. Sejer Pedersen would nonetheless like to see academic endeavours to explore new SPPS technologies.

Sejer Pedersen is afraid it would be difficult to find interested parties. ‘Funding for this kind of research is difficult to come by and the outcomes are often not considered high impact. That’s why we are urging large independent research organizations to start funding academic research programs within the area of sustainable peptide and protein manufacturing.’

But change should also be possible from the bottom up. Sejer Pedersen would like to see academics stop using substances of very high concern during their research to change the mindset of the next generation of chemists. As exemplified by the European restrictions on DMF, external motivators drastically catalyse industrial change. But why wait for an abrupt change to motivate innovation? Collins pleads: ‘Constantly innovate and be willing to think outside the box from established norms.’

Nog geen opmerkingen